Archive:Basic Tools

m (→Blade shape) |

m (→Mallets) |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

{{CaptionedImage|file=Fig76.jpeg|align=right|width=300}}<br/> | {{CaptionedImage|file=Fig76.jpeg|align=right|width=300}}<br/> | ||

It is generally easier to pivot around your little finger, so clockwise for left-handers and anti-clockwise for right-handers.<br/> | It is generally easier to pivot around your little finger, so clockwise for left-handers and anti-clockwise for right-handers.<br/> | ||

<br/> | |||

<br/> | |||

<br/> | |||

<br/> | |||

<br/> | |||

<br/> | |||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

==Mallets== | ==Mallets== | ||

| Line 49: | Line 55: | ||

Personally I tend to barely grip the haft of the mallet at all and pretty much just balance it on my middle and ring fingers, using my wrist to provide the motion and my index finger and thumb to control it. Some people grip it more firmly; others hold it further down the haft or even by the head itself. Again, there is no real right or wrong way, only the way you find most comfortable, but relaxed control and feel are key, not power.<br/> | Personally I tend to barely grip the haft of the mallet at all and pretty much just balance it on my middle and ring fingers, using my wrist to provide the motion and my index finger and thumb to control it. Some people grip it more firmly; others hold it further down the haft or even by the head itself. Again, there is no real right or wrong way, only the way you find most comfortable, but relaxed control and feel are key, not power.<br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

==Beveller== | ==Beveller== | ||

{{CaptionedImage|file=Fig79.jpeg|align=right|width=300}} | {{CaptionedImage|file=Fig79.jpeg|align=right|width=300}} | ||

Revision as of 14:19, 8 October 2012

Basic Tools

It is worth mentioning now that your choice of tools should be primarily one of comfort and not cost. You can have the most expensive, top brand maul, but if you are more comfortable using a cheap wooden mallet then the chances are that it is with the cheap mallet that you’ll produce your best work. It may sound like a load of hippy nonsense, but it is the simple truth that when working with a natural medium, be it leather, wood, whatever, the quality of your work will be very much reflective of the ‘feel’ you have with the medium you are using. Such sensitivity is greatly enhanced by familiar and comfortable tools. That said, there are times when the quality of your tools will help and they will often tend to be easier to use.

Swivel Knives

Unique to leather tooling, a swivel knife is essential. It comes in two parts, the main barrel of the knife itself and an interchangeable blade.

The barrel is definitely a matter for comfort as its action is quite unlike anything you’ve probably ever used before. The two main areas for consideration are the finger rest and the ease at which it will turn. The former is most important as the latter can generally be made acceptable with a tiny drop of oil. However, if the height of the rest is incorrect for you then you will find using the knife either becoming rapidly tiresome and a strain, or you will be unable to exert enough pressure with enough control to make a reasonable cut.

There are no magic formulae for how high the rest should be in comparison to your hand size, it’s a purely personal thing that you will only really be able to judge through use. Therefore it can be wise to invest in one with an adjustable rest and simply fiddle with it until it’s comfortable. If you are lucky enough to have one included within a starter kit that is at the correct height for you, but is an uncomfortable shape then try covering it. Anything from a piece of foam and gaffa tape, to a couple of plasters, if it works for you, it’s all good.

The blades for swivel knives however are an excellent example of where more expensive can often prove to be a wise investment. In most starter kits the blade included is somewhat broad, chunky and it is simply physically impossible to create a fine and intricate cut with it, no matter how good you are. Investing in a good quality fine blade will enhance your initial cuts, and therefore the resulting work.

Metal

There are a number of precision ground metal blades available that suit most, if not all, situations; from broad flat blades to angled blades for finer detailed work. One thing they all share in common is that they will need to be kept in good condition, regularly stropped and honed to continue providing you with a clean cut.

Ceramic

Relatively expensive, ceramic blades are generally found in almost as wide a range as metal ones. Their main advantage is that they keep a keen edge, do not need to be honed, and barely need to be stropped either. Their disadvantage is in the fact that they are somewhat brittle and so are far more likely to chip or break if knocked against something hard or dropped. When I first started tooling, I bought my first ceramic blade on the second day, and then I dropped it five years later and had to buy another one; I’ve used that almost exclusively now for well over a decade! I’ve never needed to sharpen it, and probably even only strop it once a year, if I remember!

Blade shape

If you are unlikely to be carving or tooling fine, intricate shapes or very small or tight curves then a straight blade will most likely suffice. They do require the swivel knife to be held at a greater angle (rather than almost perpendicular for angled ones) so as to cut with the corner of the blade and this is generally what makes tight curves somewhat more difficult to achieve cleanly.

Often they are also slightly thicker and are therefore capable of giving a wider cut. This gives them slightly more versatility when it comes to carving accents.

Angled blades taper to a point that enables far more intricate and fine cuts to be made. If you are considering complex knot-work, small designs, tight curves or even more pictorial carving then this is probably a more versatile blade to invest in.

Though this is a somewhat specialised blade, the ability for it to provide consistent, even parallel cuts can be an incredible time saver, especially for very fine knot-work or flora, leaf stems etc.

How to Use

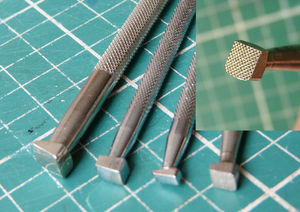

To use a swivel knife you rest your index finger across the rest and lightly grip the barrel between your middle and ring fingers and your thumb as illustrated.

Rest the knife perpendicular to the cased leather and apply pressure with your index finger and draw the knife towards you to make a simple straight cut. To curve the cut the basic action is exactly the same but as you draw it towards you to roll the barrel between your fingers and thumb to turn the blade to either side. Initially you may find it easier to make a slight curve, stop and lift the blade clear, turn the leather on your work surface and carefully reposition the blade before continuing your cut.

It is generally easier to pivot around your little finger, so clockwise for left-handers and anti-clockwise for right-handers.

Mallets

Well, technically there are hammers, mallets and mauls, though generally it isn’t advisable to use a metal hammer when tooling leather for two reasons. Firstly and most importantly, they give a very sharp strike and therefore it is more difficult to gauge the feedback from the leather. Secondly, the tools are generally made from softer alloys than metal hammers and so will deform if used with them, though this in itself isn’t necessarily much of an issue.

The difference between a mallet and a maul is basically in the shape of the head. A mallet will give you a flat striking surface and a maul has a curved one. Mauls are also generally found in heavier weights than mallets. There is no real right or wrong time to use one of the other, though you can get a greater range of strikes (by using the curve to deflect some of the force) from a maul that you can from a mallet. However, their use can be something of an acquired skill and to be honest it’s not one I’ve even felt that comfortable with so I only use a mallet. As with so much of leatherworking, it’s personal preference so if possible, try before you buy.

Wooden

Most of the starter kits you can buy will come with a simple wooden mallet. There is nothing wrong with this and if you prefer a lighter weight you may find you want to stick with it for tooling purposes. However, they are not very durable (the surface of the head can easily become damaged, so it is recommended you get an alternative for setting and any embossing, both of which are likely to require firmer strikes.

Rawhide

Usually relatively heavy, rawhide mallets can be a good alternative to wooden ones and are also more durable. The face will degrade over time but can take a lot more punishment that a wooden mallet. They can give quite a sharp strike with a fair bit of bounce to it that can be harder to control, but this does soften as the head becomes more worn in.

Nylon or Polymer

This is where the greatest range can be found. From relatively cheap, medium weight mallets to top of the range, weighted and balanced mallets and mauls. The heads themselves can be found in differing densities, and therefore give differing levels of bounce and feedback; generally the harder they are the more durable but also the more bounce-back you get. The main advantage I’ve found with poly-headed mallets is that even as the head is damaged with use, the feedback you receive from each strike remains fairly constant. Due to this I’m still using the same mallet that I bought over fifteen years ago and it still feels the same to work with as it did back then (or at the very least it has changed so imperceptibly over the years that I’ve grown used to it).

How to Use

To use a mallet (or maul if you prefer) for tooling the grip is often subtly different that if you were making a firm strike for setting for example. Generally softer grip is used, one that allows you to feel the feedback through from the leather. By that I mean actually feeling how tough the leather is, whether it is resisting the tool’s impression, whether it is solid or soft, springy or firm. It is a hard thing to describe, but trust me when I say it’s an even harder thing to feel yourself if you got your mallet in some kind of death grip. It is rare that you will need to use much more that a firm tap for tooling, and most often it will be a gentle tapping bounce that drives the tool against the leather. As such a gentle, balanced and flexible grip is essential, in addition to the fact that you will find it far more comfortable to sustain for a potentially long period of time.

Personally I tend to barely grip the haft of the mallet at all and pretty much just balance it on my middle and ring fingers, using my wrist to provide the motion and my index finger and thumb to control it. Some people grip it more firmly; others hold it further down the haft or even by the head itself. Again, there is no real right or wrong way, only the way you find most comfortable, but relaxed control and feel are key, not power.

Beveller

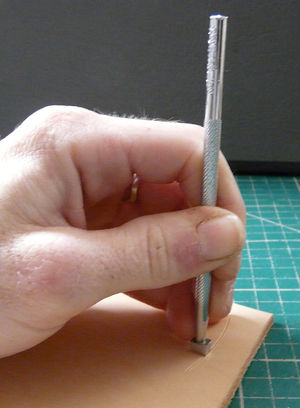

Of the three most basic tooling skills of bevelling, backgrounding and shading, bevelling is probably the most used of all. Additionally good bevelling can really lift the quality of a piece of work so it is a skill worth taking the time to practice with.

Like many ‘tooling’ tools bevellers come in a number of variations, both in size and those with a smooth or textured face and each has a very slightly different way of being used. Generally the smaller the tool the easier it can be driven into the leather and so will possibly need a lighter strike, the broader the tool, the harder the strike.

Most basic sets will contain a medium sized beveller, though if it is one with a textured face I would recommend getting a smooth faced one too as it is such as essential and versatile tool. Additionally once you’ve mastered a smooth beveller then the transition to a textured one is easier than the other way round.

Where to Use

The simple answer to this is almost everywhere! Creating borders, lifting a design or ‘raising’ a section, as a prelude to background shading, creating the illusion of an overlap (essential when tooling knot-work), all are achieved with bevelling.

The general rule of thumb is to bevel on the outside of a design, or on the side of a line where you would wish a ‘shadow’ to form. The more artistic the design, the more difficult it can be to judge which side to bevel on, but both practice and/or frequent checking back to reference material will help.

If you wish to background shade an area, it can be useful to bevel on that side of the line as it will provide you with a cleaner edge.

How to Use

Exactly how you hold the tool is another matter of personal preference, much like the mallet. Generally it should be gripped between the thumb and side of the index finger, with the tip of you middle and ring finger used as further support. Depending on the curve of the line I will tend to have my little finger both sticking out and resting on the leather, to pivot round for a large curve, or resting underneath my ring finger for tight curves or long straight lines.

The two main points are to be holding the tool perpendicular to the leather and not to have it in a tight grip that will only serve to make your hand ache after a few minutes.

The tip of the beveller should rest lightly in the cut and be struck directly down into the leather.

With each strike your fingers should act like a spring to return the tool to the same height, just resting on the surface of the leather. In this manner you gradually move along the line, being guided by the tip of the beveller along the cut. Whether you draw the tool towards you or away from you is entirely a matter of preference and you may find it equally as comfortable going either way; some people even prefer to curl their arm round so that they are working from side to side with the tool facing them. There is no right or wrong way, only your way.

To start with you may find it easier to take it slowly, step by step, a tap at a time. Strike. Move the tool. Strike. Move the tool. Strike. Making a conscious placement of the beveller between each strike. As you practice and get more comfortable with the action and confident with your grip on the beveller, you will find you think less about exactly where you place the beveller and begin to slide it gently across the surface as you go.

The ultimate in control is when you don’t need to use the tip in the cut as a guide but can hover the tool just above the leather’s surface and still follow the line smoothly.

It is advisable not to move the tool too far between each strike, instead allow each one to overlap the previous by at least half. This will help to eliminate edge marks and the second strike will help to even out the tool mark from the first and so on.

Also essential in eliminating tool marks is maintaining an even strength to your mallet strikes. One random heavier strike will leave a clearly deeper impression of the tool behind that will be harder to smooth out than if you have made a few random lighter blows.

Textured bevellers are at the same time both easier and more difficult to use. They can be easier as you can find the tool almost biting into the impressions from the previous strike, and so may find it easier to progress evenly along the line. That can also make it harder to maintain a smooth progression as the texture doesn’t allow it to easily slide along the surface, therefore developing the skill of ‘hovering’ the tool is more useful, but at the same time can give rise to mis-strikes.

Common Problem

Other than tool impressions being left along the line of the work, the most common problem with bevelling is a mis-strike. This is where the tool does not follow the line and either makes an impression slightly off to one side or the other.

If you are lucky and mis-strike on the bevelled side then it can be blended in with a few graduated strokes over it along the correct line of the cut. If the tool has strayed into the clean area of the design, then it’s a little harder to hide. Careful rubbing over with the smooth back of the spoon end of a stylus can blend light mis-strikes in, but be warned that this does subtly change the surface of the leather and will possibly be made even more noticeable with dyeing; especially antiquing which is designed to show up irregularities of the leather’s surface.

To be honest, unless you are going to attempt to re-cut your line and completely re-bevel it, I would leave the mis-strike as it is. These things happen, it’s not a flaw, it’s a design feature.

Additional Tip

If you do find that you are leaving minor tool impressions behind, it can be beneficial to run the beveller back over your work, using a firm, regular pressure to help smooth them out before you continue on with the next section. Alternatively, once all the bevelling has been done you can go over the entire thing with the ‘spoon’ end of a stylus. In much the same way, using the smooth back of it to even out any marks, though if it is in an area you will later be backgrounding it’s not really necessary; the textured background will hide the majority of marks made by a beveller. This is only tip is only really relevant to smooth bevelling.

Backgrounder

Like bevellers, backgrounders come in a variety of sizes and a wide range of textures. The most basic and oft used is a simple cross-hatched, diamond texture, but you can get some quite random ones; even a pebble effect. Regardless of the face, the manner in which they are used is the same, with the same prevision as bevellers regarding surface size in relation to strike strength.

Where to Use

Generally the point of these tools is to evenly reduce the overall surface area of a section, thereby effectively ‘lifting’ the remainder of the design. Most commonly they are used evenly within small enclosed sections of a design, for example within the lines of Celtic knot-work. However, they can be used on the edge of a design, gradually fading out by using lighter and lighter strikes, to blend in with the smooth leather surface.

How to use

The strikes required will be generally heavier that for bevelling but other than that the method for holding the tool is the same. Likewise the aim is, as far as possible, not to leave individual tool marks but a evenly textured surface; remember, it is easier to blend in a lighter area by going over it again but the only way to blend in a single heavy hit it to go over everything to match it.

As you will be covering a block area rather than following a single line there often won’t be a cut line to follow, unlike bevelling. This generally means that it is worth cultivating the ‘hovering’ action of the tool, holding and returning it to a point just above the surface of the leather after each strike. In this manner you are freer to move your hand to influence the area of effect.

Whilst this can take a measure of control that may take time to acquire, it’s not always important to be neat and ordered when backgrounding. In fact there are times when having a much more random movement can actually be beneficial.

Generally if you are filling in a small area it can be worth following the bevelled perimeter and gradually work your way inwards.

For larger areas, or when you are fading the background effect out to the surface of the leather then small circular, or more random, movements can give you a better overall effect; it is also more likely to blend in any accidental individual tool marks.

Pear Shader

Yet again, like bevellers, pear shaders are available in a variety of sizes and with either a smooth or textured face. For the same reason as the beveller this is another tool I would recommend getting in a smooth face as well if your initial kit only contains a textured one. The smooth face will allow for a good glide over the leather whereas a textured one will require a certain amount of hovering.

Where to Use

This is a very versatile tool that can quickly and easily give a real tactile lift to a piece. On plain VegTan which bruises (shows a darker colour) under impact this tool can literally shade your work. Though this effect is lost with most dyeing techniques the impressions they make, smooth depressions and channels, can make a piece just beg to have you run your fingers over it.

Often used on American western saddles and tack to give a sense of curvature to floral carving, it can do similar and lends itself very well to heraldic designs and scroll work.

How to Use

Pear shaders are held the same way as the previous tools but perhaps with a slightly stronger grip. This will enable you to smoothly move the tool over the surface of the leather as there are generally no cuts to guide you; though many designs may allow for a light dotted line to show roughly where to shade (see Tracing).

Strike strength will vary greatly depending on how deep a depression you wish to make. Remember the larger the surface area of the tool the harder the strike will need to be to make a significant impression and vice versa.

It can be used with just a single hit, or a series of strikes, gradually becoming softer as you move the tool. Due to its convex shape it is far less likely to leave a distinct edge to the tool mark, it can be easily blended in to the regular finish of the leather due to the smoothness with which it can be glided over the surface.

With textured shaders you don’t get the same glide and so must hover the tool to move it smoothly.

There is no real right or wrong way to use a shader so experiment away. You can create some fantastic undulating textures just by randomly moving it about, gliding it along or even twisting it in your grip as you strike.